This is an exact reprint of text and photos from The New York Times Magazine

The New York Times Magazine

June 26, 1938

BEHIND THE CONFLICT IN “BLOODY HARLAN”

The Background of Mountains and Hill Folk Against Which a Dramatic Trial is Being Held

By: F. Raymond Daniell

Technically and legally the coal operators,

corporations and peace officers of Harlan County on trial here at London are charged with a criminal conspiracy to nullify the

Wagner Act. Actually, however, it is the political and economic system of

that rich soft-coal field which is at the bar. For in Harlan County, as nowhere

else in the county, except possibly on the cotton plantations of the Deep South,

the visitor encounters feudalism and paternalism which survive despite all

efforts to break them down.

at London are charged with a criminal conspiracy to nullify the

Wagner Act. Actually, however, it is the political and economic system of

that rich soft-coal field which is at the bar. For in Harlan County, as nowhere

else in the county, except possibly on the cotton plantations of the Deep South,

the visitor encounters feudalism and paternalism which survive despite all

efforts to break them down.

For years the county has been known as “bloody Harlan.” It is feud country, and last year there were sixty murders within its precincts. But Harlan has no monopoly on violence and bloodshed; its designation is due rather to the fact that much of the bloodshed has been directly connected with the struggle between miners and operators and with union organizations. Because of the national interest in that warfare its troubles have received more attention than other outbursts in the feud belt.

Within

Harlan County, which lies in the southeastern corner of Kentucky on the Virginia

border, are some 70,000 inhabitants. From 16,000 to 18,000 men work in the

mines and produce from 14,000,000 to 18,000,000 tons of coal, worth $45,000,000

each year. This is more than a third of Kentucky’s total bituminous production

and, while only a drop in the national total, it is of sufficiently high quality

and is produced so cheaply under existing labor conditions that it is a strong

competitor with the product of other fields.

Within

Harlan County, which lies in the southeastern corner of Kentucky on the Virginia

border, are some 70,000 inhabitants. From 16,000 to 18,000 men work in the

mines and produce from 14,000,000 to 18,000,000 tons of coal, worth $45,000,000

each year. This is more than a third of Kentucky’s total bituminous production

and, while only a drop in the national total, it is of sufficiently high quality

and is produced so cheaply under existing labor conditions that it is a strong

competitor with the product of other fields.

It is that fact, more than the hope of swelling its treasury with several thousand new members, each paying dues of $1.50 a month, which is responsible for the determined effort now being made by the United Mine Workers to organize the Harlan miners. Unless this effort succeeds, the union fears it will lose its recognition in neighboring coal fields, where operators are complaining that they cannot maintain union standards unless Harlan County’s operators are brought into line.

Prior to 1911 Harlan County was a quiet rural community of small mountain farms. The chief industry was agriculture and logging, with a little moon shining. Even then it was known that beneath the ridges lying between Pine and Black Mountains, along the forks of the Cumberland River, there was wealth in the form of soft coal such as was needed for the manufacture of steel. There was no way, however, of getting it out to the Great Lakes. Then the railroad came.

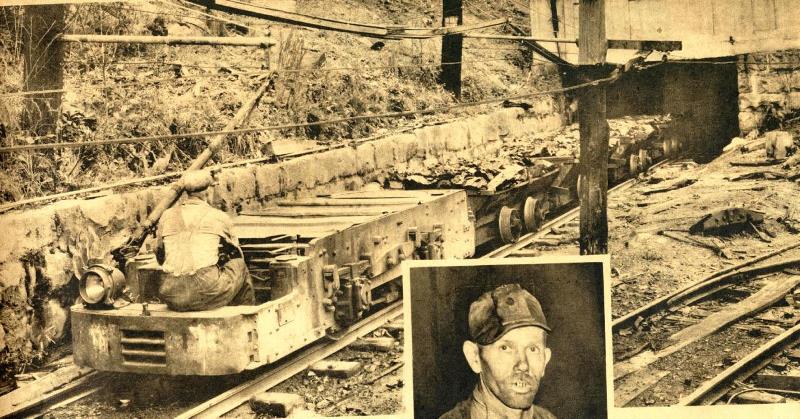

Overnight the characteristics of the countryside

changed. Here and there the beautiful green hills were defaced by the winding

conveyors over which the minded coal is carried from the drift mouth or mine

opening in the hillside to the tipple, where it is broken and sorted and sized

alongside the railroad tracks. Great piles of black waste and excavated earth

began making their appearance on the hillsides, and from neighboring counties

there came a swarm of farm boys and men, lured by the hope of high pay.  There

were no towns, no houses for the miners, except those the coal operators built,

and thus there came into being the company town and the company store.

There

were no towns, no houses for the miners, except those the coal operators built,

and thus there came into being the company town and the company store.

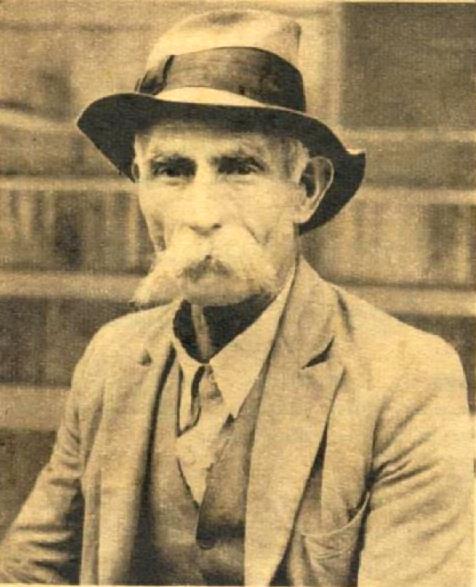

As the coal industry grew in Harlan County, local capitalists got in on the ground floor. Among them was R. W. Creech, a patriarchal old gentleman with mustaches which spread a full eight inches on either side of his nose. He had been a lumberman before the railroad came, floating his logs down the river. To him his employees are like children, to be cared for and kept in order. He is one of the defendants in the conspiracy trial. Others among the defendants flocked into Harlan County in the early days of the industry. Among them were many who went there to escape labor troubles in other fields. They brought with them a bitterness against Unions that has never died.

The camps they built for their laborers had moral standards on a par with the standards of the environment. Red liquor was drunk in Homeric quantities and fights were common. The county disclaimed responsibility for policing the mine camps, and there grew up the practice of hiring a special policeman and having him deputized by the Sheriff to lend the authority of law to his six-shooter.

Even now the mining camps of Harlan County are no week-end resorts for sissies. The industry of the peace officers in rounding up drunks on Saturday night is prodigious. The fine, usually amounting to $19.50, is often paid by the company employing the prisoner and then deducted from his pay. In the four years ended last Jan. 1, the records show that 14,000 persons went to the lock-up at one time or another-a profitable guadrennium for the jailer, who is allowed 75 cents a day for feeding each prisoner. A good manager can do it for considerably less.

For years the operators had everything their own way. But Harlan’s position in the coal business and the number of unorganized miners there were not over-looked by the Unions. There were repeated efforts to Unionize the district, and for years the Unionized miners and the operators have been engaged in a bitter feud, with not all the violence directed at the miners.

Back in 1931, when the United Mine Workers made an abortive effort to organize the Harlan field, there was competition for members among several rival unions, including one said to have been dominated by Communists and members of the I.W.W. In this period there was an epidemic of burglary of company stores and thefts of dynamite and copper from the companies, which was blamed on union members and organizers. The company put Sheriff’s deputies on their payrolls, and the killing of such deputies in a battle with strikers led to the “reign of terror” which union men say has been set up against them.

With the passage of the NRA, the Guffey Act and, finally, the Wagner Act, outsiders came in to organize the miners, and agents of the Federal Government stepped in. The world of the Harlan County coal barons began to topple. The United Mine Workers have succeeded in negotiating contracts with ten of the forty-two mines operating in Harlan County, and today the union has a office in the town of Harlan, and its field workers travel about without molestation as long as they stay off non-union company property.

Although only about a fourth of the county’s population works in the mines, nearly everybody in the county is dependent, directly or indirectly, on them. Only about 12,000 live in free, incorporated towns, and even there the influence of the coal operators is strong. The other 58,000 live in company towns, occupy company houses, walk on company streets, shop in company stores, go to company churches and send their children to company schools. Illness is treated by company doctors and justice is often administered by company magistrates, who hold court on company property. One of the big companies, until recently, had its own private jail.

The company towns range in size from little settlements of 100 or 200 houses, to cities like Lynch, owned by a subsidiary of United States Steel, where more than 9,000 miners and their families live under rules and conditions laid down by a board of directors instead of a Common Council. Here the streets are surfaced, the houses painted, and, though plumbing is almost rare as elsewhere in the county, living conditions appear reasonably good. There is a private police force and a private fire department, a smart-looking new motion-picture theatre and a department store which might be a branch of a New York or Chicago store. Lynch, where a higher proportion of workers of alien stock are employed than elsewhere, has the only Roman Catholic Church in the county.

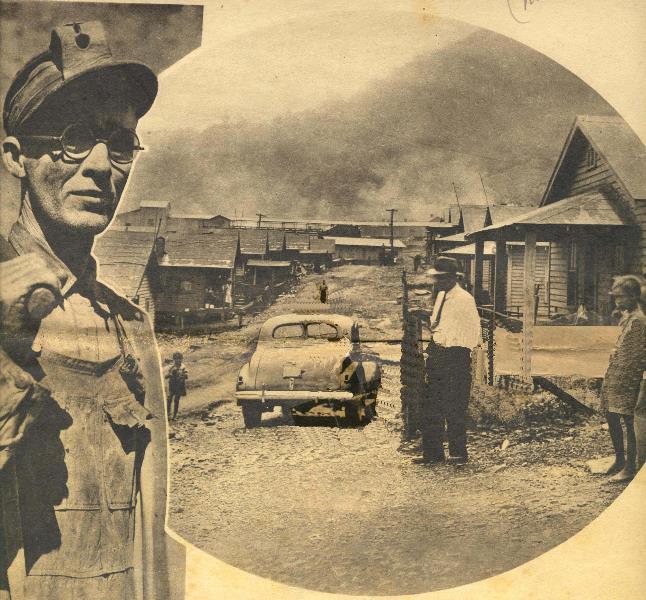

In contrast to this tree-shaded little city, with

its neat lawns and flower gardens, are the more typical towns of the smaller, locally owned companies. There the muddy, rutted streets

swarm with pigs, raised to supplement the family larder when the cold weather

comes. The dilapidated houses, standing in pools of stagnant water, and the

vacant faces of the inhabitants present a depressing picture to the visitor from

outside. Yet shiny new automobiles, in improvised garages underneath the

houses, washing machines on the back porch and electric refrigerators in the

living room are as common as in the camps where housing conditions are better.

towns of the smaller, locally owned companies. There the muddy, rutted streets

swarm with pigs, raised to supplement the family larder when the cold weather

comes. The dilapidated houses, standing in pools of stagnant water, and the

vacant faces of the inhabitants present a depressing picture to the visitor from

outside. Yet shiny new automobiles, in improvised garages underneath the

houses, washing machines on the back porch and electric refrigerators in the

living room are as common as in the camps where housing conditions are better.

In the middle of the county is the town of Harlan, a rather shabby county seat of wood and brick buildings, hemmed in, almost squeezed, by the surrounding mountains. It is one of the three incorporated towns in the county, the others being Cumberland and Evarts. Harlan’s Chamber of Commerce claims for the town a population of about 7,000, and Harlan is the shopping center for all the people in the county who have managed to scrape together enough cash to trade away from the company store. Even here, however, mine operators or their kinsfolk control most of the mercantile establishments in the town. A man can’t even buy a headache remedy without patronizing the operators, for they own the drug stores, too.

Many of the county’s people are mountain folk, quick to anger and quick to shoot. Men think no more of toting a gun than Englishmen do of carrying an umbrella. For a time, until the quaint inconsistency was corrected a few years ago, the Kentucky statutes provided a stiffer penalty for the man who merely fired at someone than for the man who wounded his enemy. Outside a little church in Harlan on Sunday night the writer saw two boys, not more than 12 or 13, with businesslike .38-caliber revolvers in their overall pockets.

The people tend to resent intrusion in their affairs by “furriners,” much as they would resent a stranger “messin’ around” their women folk. During an inspection tour of the mines the writer ordered a photographer to take a picture of a “Tobacco Road” family – a mother sitting beside her cabin with a nursing baby and an old miner resting on the back stoop and was about to ask the woman’s permission when the local photographer intervened.

“Ask the man, not the woman,” he said. “He might shoot if you ask her.”

And then on our tour of the company towns our driver stopped suddenly in the road at High Splint and began backing up. At first the reason was not apparent. Then a boulder, the size of a cabbage, rolled down the road in front of the car. Four boys stopped playing ball and retreated to the sidelines. From between two houses there came a man, his shirt torn and bloody, wielding an axe handle. Retreating before him was a man with a rock which must have weighed ten pounds. He threw it and the man with the axe handle had at him. When it was over the stone-thrower was unconscious in the road and the club-wielder was leaning against a fence, blood pouring from a crack in his skull. No one interfered or seemed especially interested.

The feud tradition is a strong factor in Harlan’s way of life. For generations it has been the custom, when a man is killed by a member of a rival clan, for all the victim’s family to go gunning for the killer and his kinsfolk. Honor is not considered avenged until the mortality score is even. Interference by the law and the courts is bitterly resented.

Relations between miners and operators have a similar directness. In the company towns, the homes of the operators generally are alongside the three and four room dwellings of the miners, who pay between $1.50 and $2.50 a month per room. It still is a common thing for the children of the operator to go to the same company school as the children of the common laborers until they have reached high-school age. As a matter of fact, it is said with some justification that mine children in company towns get more schooling than the children of incorporated towns. The county provides only seven months’ salary for the teacher, but the company town usually pays the teacher for keeping school open another two months. The schools are built by the company, but the teacher is appointed by the Superintendent of Schools.

The owners of the mines dress in khaki work clothes, go in and out of the mines and sit in an office, usually on the ground floor of the commissary, unguarded by secretaries. Any worker is free to come in with his problems whether they be financial, domestic, or legal, and he usually can count on receiving help if he has kept clear of the United Mine Workers.

The mines pay off every two weeks in cash, and when times are good the miners of Harlan County make relatively good money, receiving from the open-shop mines a little above the union scale, but working longer hours than union men and having no means of checking company figures on the amount of coal they dig. Most of the financial transactions between the miner and the store are carried out by means of scrip issued to the employees against credit they have established by their labor under-ground. This scrip is non-transferable, and, generally speaking, can be spent only in the company store, where prices are slightly higher than in the cash chain stores downtown. Everything from the finest quality meats and canned goods to the latest in overstuffed furniture can be bought there. Many of the commissaries sell liquor, which is legal in Harlan County.

Credit is available in almost unlimited amounts to regular employees of the mines, whether the mines are running or not. When they do run, the operator knows his men will dig coal and he will sell it, deducting the amount he has advanced from the pay due the miners. Most of the company stores now have about an average of $20,000 outstanding in over-drafts of miners, but they are not worried.

In one camp this correspondent was permitted to inspect the ledger in which the miners’ accounts are kept. One entry showed that one of the miners, after all the credit advanced to him had been deducted from his earnings for a month, came out exactly even with the company. Closer inspection showed that he was paying a lower rate of rent than the other miners. When the treasurer of the company was asked about this, he explained that the amount this man had earned last month was a little less than the credit that had been advance him so the company cut his rent by a few cents to make it come out even.

In Harlan a miner who “keeps shet” of union activities need not worry about keeping a roof over his head, nor need he concern himself much with where the next meal-or, for that matter, the next drink-is coming from, for the paternalistic employer provides a kind of social security.

Harlan’s leading citizens are anxious that this side of the picture be presented.

Such are the setting and the background for the drama in the court room here in London which the whole county has been watching. Harlan today sees what may be the climax in the struggle between two sharply differing ways and philosophies of life.

Talk to the operators of the mines and you will hear that they want to protect their miners from being forced to join a union which they do not want and which, they say, for all the dues collected, cannot give them anything they do not now receive without the necessity of paying dues. You will also understand that the operators want to run their mines without outside interference.

Talk to the union leaders and you will hear that they are fighting paternalism of the operators. They charge that the one thing a miner may not do on company property is think for himself or speak out in public. They are fighting, they will tell you, to free the miners from an archaic system in which liberty has no place.